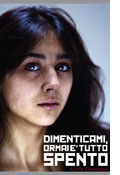

The look of abandonment. Faces and words of the abandoned children of Romania

Forget me, now it all off is the result of several months of field work in close contact with the daily life of many abandoned children. Why go back today on a subject as painful as the separation of parents and children at the time of Ceausescu, perhaps many Romanians prefer to bury the rubble of a past world?

I arrived in Romania almost by accident, through the European Voluntary Service (EVS). I found myself out in the evening to bring hot tea in winter to the guys who took refuge in the sewers and in the empty houses. As my understanding of the Romanian language is also honing the dialogue, whispered around a plastic cup boiling water became deeper. I began to ask the guys that I met what had happened to him, because they were so many to take refuge in the darkest corners of the city and desolate, lonely, homeless and without family. The answers to my questions came in a discontinuous way. Sometimes we put months to get the occasional word, others I came across in the desire to tell those who are used to being ignored. Their words, which invariably ritracciavano a history of neglect and poverty, brought me to mind echoes of confused images seen on television as a child back in '89. The guys I was talking to, all mostly my age or a little younger, they were the children whose images were upset and shocked the international public opinion to the fall of the regime, so as to cause a wave of international adoptions. All those pictures, yet often in black and white, of malnourished children in the beds of orphanages, of kids slumped on roadsides, reappearing in the present.

The ceausei, so they were called the abandoned children in hospitals and orphanages, took the state and entrusted to the care of the state. Today, they have become teenagers and adults, they sleep in the sewers, in the stairwells of apartment buildings and empty houses. Wander with bags of glue, bottles and syringes. They work for the day in the parking lots, from florists or unload goods to markets. Often wear dirty clothes because they live on the street, eat care centers and eke between begging and petty theft.

This is what everyone knows, that which is easy to see through to the Gara de Nord in Bucharest.

This is not what I wanted to tell.

Photographing the daily lives of these kids today, meant to show a result, without giving due weight to the historical and political reasons that caused it. It meant feeding the cliché of violence and misery, without finding out what lies behind the scenes. That's why the choice to revisit the past through the memories themselves of these guys, witnesses unaware of the revolution and of the failures of the twentieth century. Their words, full of anger and sadness, make us breathe the cold air of the orphanages and the fear of the nights spent on the streets. Retrace the memory of a personal and collective that has engulfed an entire generation of mothers and children. Those mothers so often evoked by their stories as a souvenir vague and indelible; the violence of the fathers and the bite of hunger invoked as the physical sensations still tangible. How are tangible, for the reader who is preparing to browse this book, their young faces and deeply marked where there is no room for carelessness. A gallery of expressions, with one glance, "say" the loneliness and rejection. A skin from which emerges the fragility, insecurity, anger and courage.

The courage of those who, marginalized and rejected since the early years of life, he decided to tell their stories without shame and without filters.

"The channel of the sewer was very long and we were several to stay there. I had placed a corner at the bottom and stuck in the walls of the postcards and photos. I had chosen quell'angoletto apart to stand on the sidelines and do not meddle in the affairs of others. We had water, the same one that comes in the home. When I washed the clothes I laid them out in a point from which hot air and dried in 10 minutes. Then the channel has been closed. When I work on construction sites. I learned to do the floors and a whitewash. I like to work, any work, but I do not have the documents and can not be taken in good standing. My mother died when I was a kid and my dad left me at the orphanage at the age of four years. I need a birth certificate to get an identity card but the last time I went home to retrieve my father I was not even allowed to enter, is an alcoholic and violent. "

D. 20 years, born in 1987

"I was abandoned at birth in hospital. I grew up in a placement center. I saw my mother for the first time at the age of sixteen. He worked in a bar and went to look for her. When I saw it has been as a sort of surprise. I wanted to talk to her but she would not. I asked her to take me home, told me that he had debts and you killed if not solved them. He told me he did not want to keep me and who had remarried with another.

Then I asked her some money to go back to school, in Timisoara. I never see her again. I have changed many institutions: Azur Victoria, Judeţul Timiş number 2, Logos Judeţul Timiş number 10 From there they fled and went to a health emergency for street children. I stayed there two years, then I moved Generatia Tinera Institute of Timisoara. I stayed there four months, and then I have interned in a psychiatric hospital. I have interned because I wanted to have a pension. I was twenty. When I came out I took the train and quickly came to Bucharest where I went to another school. "

D. 22, was born in 1985.

"They left me in the hospital. I do not know anything when I was little. I attended twelve years in the Special School of Balş. I beat a girl, Madalina. She was a girl of my own age. I have not played. I was afraid of her. Madalina I took the money and I said nothing because I was afraid. In 1999 I finished school. I liked school, I did not like this girl who always beat me. After Balş, I went to another center for disabled children. I've always gotten along with the ladies of the orphanages. I do not know who my parents and I do not even know it. I want to work and I like sports. I would like to be a sports car, I did some competition and I won a prize in athletics. I do not want to build a family. I do not trust anyone, it's hard to find a man who care about you and I'm scared. I have a good friend in Corabia, medical assistant thirty-two years. When I miss the phone today. The center of Corabia I liked it because they had more care of us. I am sick of chronic gastritis because they ate, drank coffee and smoked on an empty stomach. I started smoking at age six. I have always lived in an orphanage and I had not the courage to leave, I did not know what was out and I was afraid. "

V. 34 years old, born in 1979.

Giada Connestari(For information about the author and his work, cliccare qui

http://www.orizonturiculturale.ro/it_interventi_Giada-Connestari.html

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento